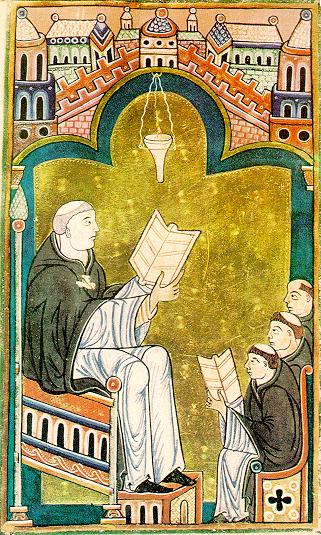

"The man who finds his homeland sweet is still a tender beginner; he to whom every soil is as his native one is already strong; but he is perfect for whom the entire world is as a foreign land." -- Hugo of St. Victor, Didascalicon iii

This twelfth century monk knew what he was talking about. He'd come as a boy to Paris from Saxony. The French city did not feel like home to him. He disclosed to students who might have suffered from a similar homesickness: "From boyhood I have dwelt on foreign soil, and I know with what grief sometimes the mind takes leave of the narrow hearth of a peasant's hut, and I know too how frankly it afterwards disdains marble firesides and paneled halls."

Hugo of St. Victor was himself "someone for whom the entire world is as a foreign land." In short, he was a pilgrim, "peregrinus," and he leaned on an image from his Augustinian training. In his "Confessions," Augustine used "pilgrim" to describe the Christian's sojourn on this earth, a spiritual displacement. For Augustine had experienced a physical displacement similar to Hugo of St. Victor's when he left North Africa to continue his studies in Milan. There he encountered the cultural disdain people reserved for someone born in one of the Roman colonies in North Africa. Like Hugo of St. Victor, Augustine was spiritually and physically a "pilgrim."

For my part, I feel spiritually at home, maybe more so than in Berkeley. The dominant place of worship on Sundays is not the coffee shop, where Berkeley gathers its devotees of the Church of the Latte Day Saints. Here lots of people are in church on Sunday. And many of those who aren't, are at the mosque or synagogue on Friday. There's a spectrum of practicing believers, with a richness I'm just beginning to appreciate. It's not the dismissive divide between the "churched" and the "unchurched."

Such worship is not just habit: a deeper mystery sustains it. Something gets people through these fierce winters; something animates their evident civic spirit; something engenders ready discussion of a common good. So spiritually, this feels like home, and I can't share Hugo of St. Victor's spiritual displacement.

But physical displacement registers keenly. Though I love the skyscape and its palette of gunmetal blues, it's not home. The river is mighty, but it's not the grey Atlantic. And I fiercely miss friends and family in Delaware and the Bay Area, but I can't imagine them here.

Nor does being in any of these other places satisfy. I'm eager to get back, because I'm supposed to be here. More accurately, I'm called to be here. But home is not where your mail comes, nor is it where you have a job. Home is not even where you've found a calling. I'm honestly not sure "what" it is, possibly because I'm not even sure "where" it is -- at least not at the moment.

Is this the "perfection" Hugo of St. Victor was talking about? I won't aim for so lofty an ideal. But the image of the pilgrim is consoling....